Revisiting Our Rate Outlook

As the 10-year Treasury trades near the low end of our current range of 4.3% to 4.5% and we digest jobs data and prepare for the Fed, it seems like a good time to revisit and restate our outlook for rates.

Political Reaction to First Fed Cut

Before going further, it makes sense to take a look at the likely political reaction to the first Fed cut. Why? Because, I for one, believe that it will influence the timing of their cuts this year.

- Former President, and presumptive Republican nominee, Donald Trump, is likely to use social media and the campaign trail to claim that the Fed is handing the election to the Democrats. In addition, the cut is politically motivated to help the current president, despite a failure to get inflation under control.

- Current President, and presumptive Democratic nominee, Joe Biden, is likely to claim that Bidenomics is working, the country is in great shape, and the Fed cut is confirmation (if not affirmation) that his policies are working.

- Some percentage of the population will believe each narrative, and that is important.

Maybe the Fed won’t take this into account, but for me, I would not make the first cut in September.

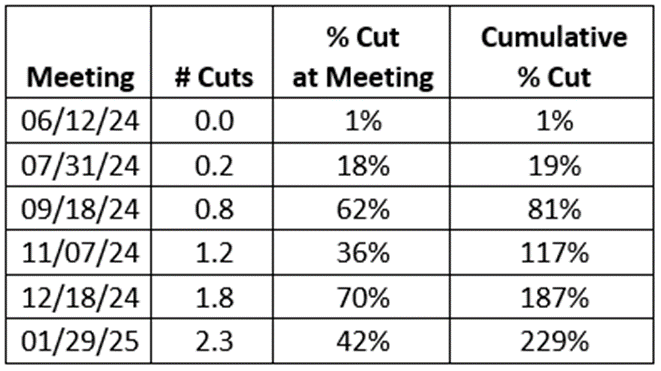

Fed Probabilities

Using the WIRP function in Bloomberg, we can examine what the market is pricing in, as of Tuesday June 2nd.

The market clearly disagrees with me, as the market has September as the largest probability of a cut before December. Cumulatively the market is pricing in an 80% chance of a cut before the election.

I believe the Fed wants to cut once, as it would be a confirmation that their policies have worked. That they tightened appropriately, and slowed inflation down to the point that they can start going the other direction. They did all of that without tipping the economy into recession.

Given the long lag effects and the desire to demonstrate their successful policies, the Fed will give us a cut this year, almost regardless of what the data signals. If the data is too strong, they might not cut, but it has been equivocal at best.

So, I like a cut at the July meeting. 25 bps is my base case, with a possibility of 50 bps if the data is weak enough (which I suspect it will be on the jobs front).

I lean towards July rather than September because, while the Fed will see the same political discourse about their cut, it will be far enough away from the election to mitigate the political noise, and it is peak holiday season, making it less likely that the noise will be heard.

From there I expect another 1 to 2 cuts this year, presumably November and December.

I am basically in the 75 bps camp for this year (with either 2 or 3 cuts), starting sooner than is currently priced in.

We will get an updated Summary of Economic Projections at the June meeting.

On the dot plot front, I am looking for the median to move to 2 cuts, and to be in line with the mean that dropped in the prior release. So, I’m likely going to be fighting the dots.

Look for Powell to put July firmly on the table, which would also be fighting the dots (but he often does that).

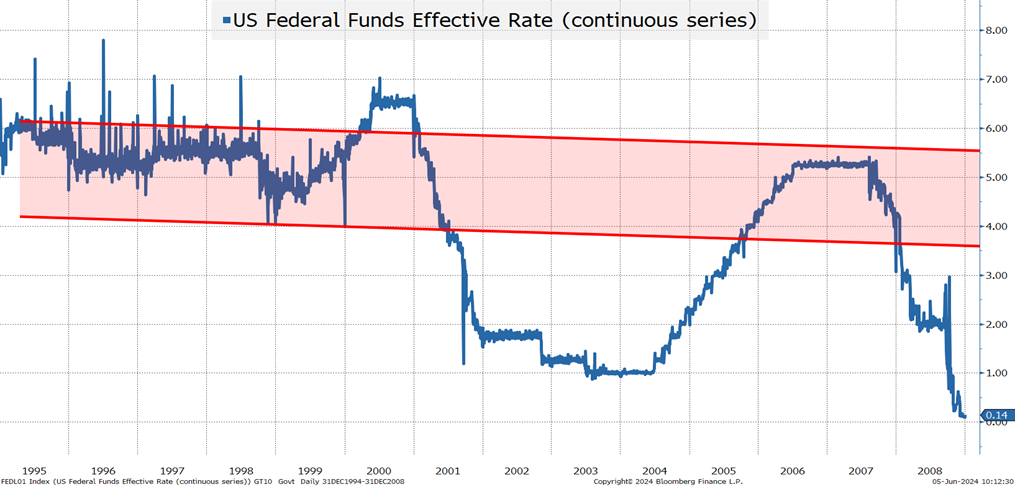

Look for 2026 and the “longer run” (presumably the terminal rate) to inch higher. There has been enough discussion about R* in recent weeks for the Fed not to question what the appropriate level of longer-term yields should be. Similarly, there is enough debate about whether current yields are restrictive at all (not just restrictive enough) that there is likely to be an incremental move to Normal for Longer.

While we have lurched from financial crisis to financial crisis in the past 15 years, maybe we have lost sight of what used to be “normal”? Maybe something well above 3% is “normal”? Will the AI productivity boom not allow for growth with higher rates?

It is probably a touch early to be fixated on the terminal rate, but I think that will become a more captivating topic once the Fed makes the first cut.

I suspect as that happens, that terminal rate projections will increase AND we may finally see some “normalization” of the yield curve.

Factors “Good for Yields”

There will be pressure on yields from many sources, and in many directions. This will include data and policy that influence yields, the shape of the curve, etc. The list is huge, and probably includes things I haven’t even thought of, let alone discussed, but let’s take a stab at highlighting what seem to be the most likely influences.

Good for yields, to some degree, means “bad” for the economy.

- I have two working assumptions on the jobs data that I think point to a weaker employment situation than the market (and even the Fed) is pricing in.

- The Birth/Death model relies heavily on EIN creation to anticipate job growth. There is reason to believe that as the “gig” economy grew, more people have taken advantage of creating companies or LLCs for their “gig” work. Also, as discussed in More “Exceptionalism”, the percentage of jobs created via this model versus other sources of job creation has increased dramatically. The “plug” has become more important relative to the total, which gives me concern about the reliability of previous jobs data.

- Seasonal adjustment. I will drag the poor Chicago PMI data into this discussion. The main argument for ignoring recession-like Chicago data is that the economy isn’t as manufacturing focused as it once was. True, but in theory, we are trying to be more manufacturing focused again. The second argument is that Chicago isn’t as important as it once was. I agree with that as well, but it makes me wonder how many of our “seasonal adjustments” are based on long-term trends that are no longer as dominant as they once were (housing construction in the Northeast being one example). As we have seen large geographical shifts in terms of residency (and presumably jobs) over the past few years (a massive uptick during and post-COVID/peak work from home), there is a risk that seasonal adjustments have not kept up. That we “add” jobs in the cold winter months and “take away” jobs as the summer approaches, could be a mistake. That is in addition to all the other difficulties surrounding “seasonal adjustments” when something like COVID ripped through the economy, first destroying jobs, then re-creating them or replacing them, as the economy re-opened. Even in today’s ISM services report, employment was weak (below 50) for the 4th month in a row (and for 5 of the last 6 months), and it hasn’t been at 51 or higher since last September (but don’t tell the NFP that).

- While the SAHM model has not been triggered, I think that there is a chance it will be. However, it “amazes me” that “unemployment” data relies on the Household Survey, which no one seems to care about for anything else.

- The insatiable consumer. Most “perplexing” of all is how incredibly resilient the consumer has been. Is that finally changing?

- Credit has been soaring and is above trend (and that doesn’t include “pay as you go” options). While the wealthy continue to do well, there are increasing concerns about the ability of the less affluent to continue to spend (and the definition of less affluent may be ratcheting upward as housing prices in many regions are in the “unaffordable” range).

- Spending on inflated prices. If something you needed cost $1 two years ago and costs $1.20 today, then you will spend more, but you aren’t getting anything more. This is problematic. Increasingly, my concern is that “official inflation data” says that a good “only” costs $1.10, which might explain why virtually every survey of individuals expresses a lot more concern about inflation than economists (or even the Fed) seem to express.

- Relatively high bond yields with a strong currency. On a quick scan of bond yields, the 10-year at 4.3% is still higher than in the U.K., any major economy in the EU, Japan, South Korea, or even China. At the same time, the dollar has seen strength (DXY, a measure of the dollar versus a basket of currencies, is off its highs, but it has performed well). Getting an “above market” yield in an appreciating currency is not a bad thing (though how many investors can take advantage of that is a question for me).

- Competition from China and growing production in India. As anyone reading the T-Reports knows, Academy has been very focused on The Threat of Made By China 2025. That will lead to pricing competition versus Chinese brands, which should put a damper on inflationary pressure, at least on goods. India, which we have also made great efforts to highlight, could also help reduce production costs across the globe.

- Decreasing demand for goods and services. My inbox looked like it did pre-COVID recently – stacks and stacks of e-mail (not all of which made it to junk) touting Memorial Day sale after Memorial Day sale, and now with “extended Memorial Day” sales. I am not worried about goods inflation and think that will help keep a lid on yields.

There are some pretty powerful forces supporting bonds, which should help on yields.

Factors “Bad for Yields”

What could push yields higher?

- The Deficit. The Deficit. The Deficit. The Deficit. The Deficit. The fact that the increasing deficit manifests itself in seemingly ever increasing auction sizes doesn’t help, but that tends to be a trickle that can be overcome incrementally. It is the moment that investors “throw up their hands” (in disgust) that pushes yields much higher, much faster. Not only does no candidate or party (at any level) seem credible on deficit reduction, very few even seem to be talking about it with anything resembling a straight face. The Deficit. I am not sure how and when the deficit takes center stage, but when it does, we will have seen prolonged spells of weakness in Treasuries, leading to higher yields. We can all watch every auction and determine what to do next, but that isn’t the problem. The problem is when too many investors get too worried all at once and reduce their purchases (or start to sell). Quant funds seem particularly adept at pushing yields higher, as investors keep getting sucked into a “duration chase” during the initial stages of higher yields. I highly suspect that now that the Trump trial is over, and we seemed to have hit some sort of status quo in the Middle East and Ukraine (not necessarily a good status quo, but a status quo nonetheless) we will focus on the campaigns and deficit discussions will re-emerge as a good talking point. Let’s not forget, there is an entire cottage industry of doomers out there, prepared to pile on to any concerns about deficits.

- Less demand from foreign buyers. While we see the potential that high yields overall, coupled with a strong dollar, could support markets, there are reasons to fear that other pressures might overwhelm that advantage. China, whose bond holdings have been shrinking, is likely going to need money to stimulate their economy, further shrinking their holdings (plus, they may be preparing for a prolonged trade war with the U.S. and having fewer Treasuries would be good from their perspective as “we” cannot weaponize their holdings). In Japan, it might be as simple as 1% is enough. If you can get 1% in JGBs and need returns in Yen, is the simplicity enough? Why bother going through a series of complex FX hedging trades to get higher incremental yield when 1% is enough? Many foreign buyers of Treasuries don’t want the FX risk, therefore minimizing the benefit of a strengthening dollar. I suspect that “getting enough” in your own currency will be more important than other factors, especially in Japan, which will weigh on bonds and hurt yields.

- The risk to commodities. In theory, and in keeping with Academy’s strength, we could label this as Geopolitical Risk (see Geopolitical Risks, Perception vs Reality). I am increasingly concerned that we will see an action taken this summer that will create problems or some major commodity SNAFU (energy or industrial commodities in particular). There seems to be no easier way to disrupt our economy, or get a lot of domestic finger-pointing, than using inflation (as our Achilles Heel) against us. Maybe it isn’t in anyone’s interest to disrupt the apple cart like that, but that seems naïve in a world of heightened geopolitical risk, where the recent social media storms around the Middle East and former President Trump’s conviction have likely been added to the playbook of misinformation that our adversaries may use against us. Finally, if India can continue their trajectory of growth after their recent election, this economic growth could be inflationary over time. This would be a balancing act between cheaper goods helping as they come from Indian production, versus the increased demand for goods and services from an increasingly wealthy Indian population.

- On-shoring. Near-shoring. Existing government subsidies. Energy demand. Many things that will ensure national security on a level that goes far beyond traditional military security will be inflationary. They are necessary, good, and should be welcomed and pursued, but that doesn’t stop them from being inflationary during the build-out stage.

I believe that the negatives outweigh the positives for yields going forward.

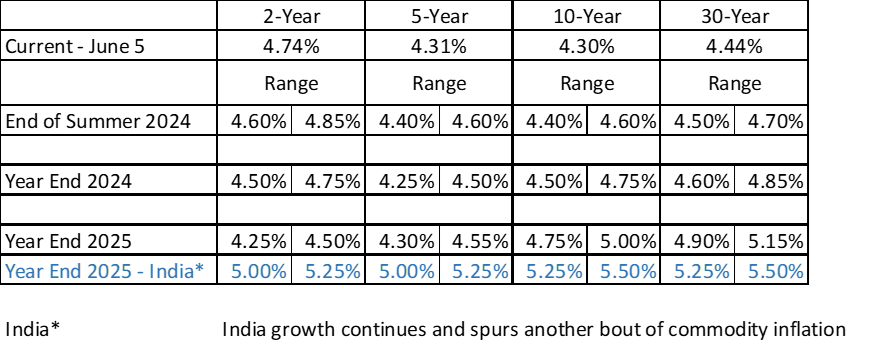

Yield Forecast

For the coming days, up to and including the Fed meeting, my base case is that we could see lower yields. I expect the number of cuts to bump to 3 by the end of January 2025, and the timing of cuts to be pulled forward (July for the first). The 10-year could drift as low as 4.2%, but that would be a stretch and I would be preparing for higher yields as we break through 4.3%.

With one caveat, that sometime between now and year-end, the 10-year will break 5% again.

Investors should be taking advantage of the recent rally in bonds, while issuers should be issuing whatever they need as Treasury yields and credit spreads are favorable, and that outlook gets murkier the closer we get to the middle of the summer!